Are People Of Colour Talking Enough About Mental Health?

Grace explores how BME communities talk about mental health.

Under-represented in child and adolescent mental health services, yet over-represented as adults, Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) people are most likely to go into crisis before they get help. What’s causing this? Are BME communities really not talking about it?

In BME communities, there’s a spirit of ‘coping’ and ‘just getting on with it’.

In exploring this topic, I’ve found people of colour do talk about mental health. What we need to consider is how.

In BME communities, there’s a spirit of ‘coping’ and ‘just getting on with it’. This is one of the reasons stories praising ethnic minority children excelling in schools ahead of their white counterparts. Or why so many own their businesses. Pressing on and getting things done is the status quo and it’s been a successful way to function a very long time.

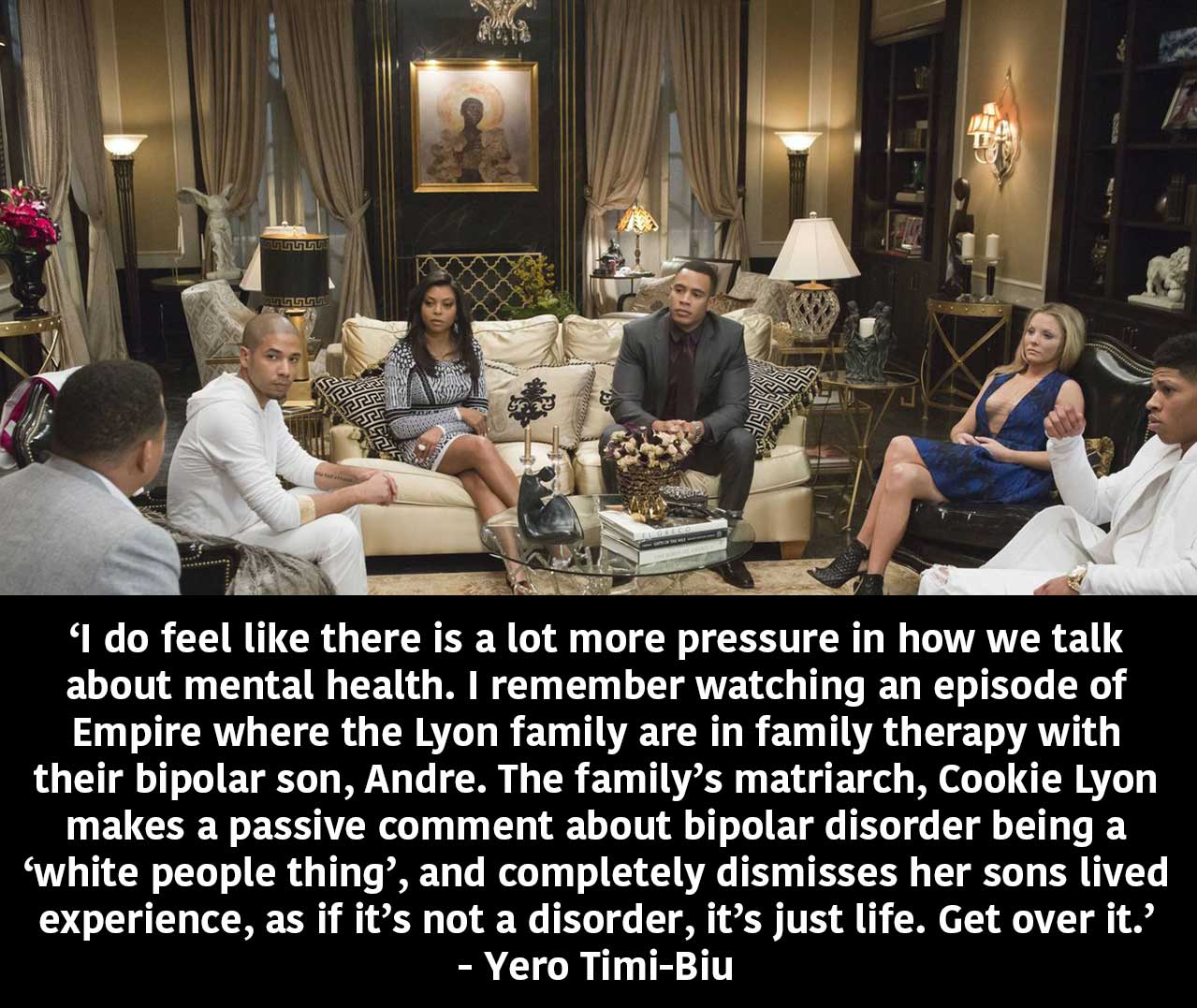

However, that attitude has been normal for so long that we need ask what we’re ‘coping’ with, or’ just getting on’ with. Over email, screenwriter and producer Yero Timi-Biu discussed the pressure – particularly on black women – to do exactly this. ‘[We] are often painted as indestructible and strong *cue ridiculously redundant memes about being a strong, black, independent woman* so it may be hard to seek help when we need it.’ In this instance, even mainstream culture reinforces the idea that black women should essentially be emotionless machines and if their not, they’re failing. It’s burden that can be damaging when people hold themselves to this impossible standard. As a result, people can’t recognise when they need help.

The language used also extends to how mental illness is identified in others. Within BME communities, having people live with you – grandparents, parents or other members of the family or the community who need support – is so common it’s almost expected. Yet, the people who care for these individuals wouldn’t identify themselves as carers. Though they are eligible for support – emotional and financial – they’re seen to be doing the right thing. If the reaction to push through any problems out of the kindness of ‘just helping out’ kicks in, it’s potentially another barrier against the carer seeking further help.

In other cases, normalisation of behaviour can prevent people from identifying symptoms. They may see the effects without linking them to disorder. In a conversation with Shanade from ZAZI, we discussed how BME communities are sometimes casual about mental health. Elements of mental illness become so familiar that young people grow up thinking it’s different, but normal. ‘Oh, he’s always a bit sad’ or ‘she just doesn’t really like to go outside.’ The language used suggests that’s it’s not serious. In contrast, words used in professional settings are so drastically different that people don’t always make connections between the two.

In my opinion, there’s a generational gap in knowledge. Closure of youth services that address these issues means that young people have to rely on self-education. Schools teach PSHE, but there are still calls for more detailed mental health education. Lack of official education has created a positive discussion around personal mental health. However, deprived areas that relied on services that were cut have been affected. On the other hand, our parents’ generation seems to be able to identify symptoms attributed to mental health disorders.

BME communities are sometimes casual about mental health. ‘Oh, he’s always a bit sad’ or ‘she just doesn’t really like to go outside.’

Ailsa Fineron is a photographer of mixed Chinese and Scottish heritage and acknowledges her parents’ ability to identify and support her. ‘I’m from a very medical family …so when I had my first major depressive episode both my parents took it as seriously as if I was physically ill. [They’ve] always validated me when I feel I’m not deserving of treatment’. Yero’s grandma was bipolar, which prepared her mum for supporting her with her depression. ‘Having a mum of my own who understood what it was like to both go through depression, and see someone else live with it really allowed me to speak freely about how I was feeling, and it made my parents check in on me frequently.’ Knowing that there are parents and other older people out there who can support young people affected by mental illness is great, but what about those who don’t necessarily feel comfortable accessing the services or can’t identify symptoms for themselves?

Firstly, it’s important for people of colour people be able to identify what mental health and illness looks like in our communities. If we can spot symptoms within our own cultural practices, we won’t discount what we see or how we feel. However, there are still factors outside of our control, as show in recent cases. ‘Over 90% of people with mental health problems from Black and Minority Ethnic communities experience discrimination.’ The government needs to bring in measures to ensure that when people of colour do use the services, they’re not suffering any more than they need to.

What can be done to help?

By talking and being equipped, we can look out for each other and hopefully, do more than just cope.

Bristol-based group ZAZI is doing something right. A partnership between Off The Record and Nilaari, they work with young BME people in their communities. Although they talk about mental health and well-being, they don’t shy away from the many other issues that affect young people of colour. They also discuss feeling safe, positive role models, drugs, criminal activity, and events like stabbings affects more than just the people involved. Shanade tells me, ‘[they] see most of the mental health within [the BME] community as a symptom of the wider problems. ZAZI seek to explore these problems with young people and increase their knowledge and understanding and support them in their journey.’

Mental health in the BME community and society in general has come a long way, but there’s still more to be done. Young people of colour shouldn’t have to hold ourselves to impossible standards, or feel like we don’t need or deserve treatment or help. As we campaign on matters outside of our control, we need to keep talking about what we can control. Yero intends keep the conversation going: ‘I am proud to be an advocate of mental health awareness, especially within BAME communities and hope we can create more safe spaces for people to feel supported.’ By talking and being equipped, we can look out for each other and hopefully, do more than just cope.

Find out more about Zazi here.

If you want to do something about mental health, consider volunteering for Mentality.

Do you think people in your community are talking enough about mental health? Talk to us – @rifemag

Done some talking? Try dancing next